Blog

Breaking chains, Forging Links, South Africa, September 2025

Dr Simon Hyde

CEO, HMC

Read the blog

The opportunity to visit South Africa came about thanks to an invitation and a celebration.

The invitation came from Lebogang Montjane, the larger-than-life Executive Director of ISASA (the Independent Schools Association of Southern Africa), who invited me to the Annual Conference of SAHISA (the Southern African Heads of Independent Schools Association). The celebration was the chance to mark Antony Clark’s retirement from Michaelhouse after six years of distinguished service and a remarkable twenty-seven years in HMC. HMC’s 2030 strategy embraces the global nature of education and recognises the enormous value our international members bring to the association. International trips are not just an opportunity to acknowledge that contribution, but also to reach out and learn.

My only previous visit to the Rainbow Nation had been in 2002 when an extremely generous Tony Little, then Head at Oakham, had given me three weeks’ leave to attend the World Schools’ Debating Championships in Johannesburg. I was one of the national judges and one of Oakham’s debaters was part of the England team. South Africa had only recently broken the chains of apartheid and those three weeks in January remain amongst the most memorable experiences of my life, and not only because a cold English winter was transformed into a glorious South African summer.

Nine South African schools have at one time or another been a part of HMC, though sadly today only one, Michaelhouse, remains in membership. Visiting Cape Town for the conference gave me the opportunity to visit a founder member of the international division, Bishops Diocesan College. When the international division was founded in 1921, two South African schools joined, Bishops and St Andrew’s College, Makhanda, formerly Grahamstown. These early international HMC pioneers, like their fellows in Australia, Canada and New Zealand, were all boys’ schools, many of whose alumni had recently fallen on the battlefields of the Great War. Antony William Scudamore Brown was one amongst far too many. He had been the Rector (Head) of Michaelhouse since 1910 and was killed on active service in 1916. Indeed, it was probably the war that provided the opportunity for school leaders from across the world to meet and connect (or reconnect) with HMC.

My first school in Cape Town, however, was a girls’ school, the legendary St Cyprian’s, or St Cyps as the locals call it. Presiding over the school is the remarkable Shelley Frayne. Our hour with her senior team shot by and gave me my first surprise when I learned that VAT had travelled with me to Africa! Rather than introducing the levy, however, the South African government is trying to remove VAT from educational enterprises or schools’ trading activities. So far, so good, but there’s a problem. As Mogola Makola explained later at the SAHISA conference, for schools that are registered for VAT, de-registering triggers a tax charge on the value of the school’s assets, which for some schools is likely to run into millions of rand. ISASA is of course making representations to government, but the uncertainty is always a worry.

The theme of the SAHISA Conference was ‘Breaking Chains, Forging Links’ and it was an honour to be invited to address the delegates and to bring fraternal greetings from HMC, hopefully more in the spirit of forging links than breaking chains. The conference had been planned by a regional organising committee led by Conference Chair Neville Ontong and with the SAHISA Chair, Lisa Palmer, in support. SAHISA (the Heads’ association) is a constituent part of ISASA (the national body), to which schools pay their subscriptions (based on school category, the wealthier schools paying more). The Heads’ association has a small staff and depends heavily on the members to run the conference, though the much larger ISASA staff provides logistical support.

SAHISA has over 400 members, who are the heads and principals of ISASA-affiliated schools. It is a very inclusive organisation with prep, high and all-through schools represented from all sections of the Southern African independent school sector. As John Huggett, one of the organising committee commented, the purpose of the event was ‘to gather, to reflect and to grow together’, sentiments that would not have been alien to Edward Thring at Uppingham in 1869.

The conference started somewhat prosaically with the ISASA AGM, though it was rapidly followed by Lebogang Montjane’s presentation on global political and economic trends as befits someone with degrees in history, government, education and law. The picture was not entirely encouraging with the end of the Pax Americana, the prevalence of global tensions, uncertain new alliances and anaemic economic growth. It was again John Huggett who reminded us of Longfellow’s words,

The best thing one can do when it is raining is to let it rain.

Speaking second, after a technical hiccup, Nthime Khole, ISASA Chair and managing partner of a private equity firm, presented an association overview. Of South Africa’s 13.5 million learners, 740,000 or 5.5% were in ISASA’s 822 South African schools, a small decline from the previous year attributable partly to school closures, but also to terminations due to issues with educational quality. Key to ISASA’s work is quality assurance as well as professional development, legal support and government and stakeholder engagement.

Whilst South African structures may be different, much of the activity would be very familiar to HMC members. ISASA’s 2030 strategic plan (yes, they have one too) sets out their desire to be seen as contributors to the educational ecosystem and to improve communications. They are in the process of reforming their governance structures and ISASA is evolving from a membership organisation to become a limited company. Amy Naicker-Morrow, ISASA’s data analyst, shared plans that again will be familiar to build a better CRM, to gather data directly from schools through a portal and to enhance the surveys of school benefits, employment equity and the vital tracking of transformation and diversity. As at HMC, new technologies are enabling real time dashboards to provide much greater clarity about trends and timelines.

The conference format was also familiar with keynotes, breakaway sessions, sponsors and exhibitors as well as the gala dinner, at which a number of retiring heads bade farewell to the association. Most speeches (the length of some of which would in truth have tried the patience of certain HMC members) reflected on their careers and the changes they have seen, not just in education, but in their association. In a very honest contribution, one Head admitted he was retiring early, tired of the many pressures of headship which sounded all too familiar. This was not, however, the majority view. For all, it had been a real privilege to serve as a head and to have given many decades of service through a rapidly changing period of South African history.

The first keynote speaker was Pastor Dr Braam Hanekom who spoke about his work in transforming communities. In 1994 with the formation of a new democratic government, South Africa had created a state, but not a nation. Questions around identity persist as many continue to live with an ‘apartheid mindset’. New beginnings, we were told, were always messy and change takes time. ‘It’s not about fixing potholes, but about healing people’ and restoring the web of relationships based on shared values. Of course, schools must play a central role in that journey. But tensions abound. Take for example the Ulwaluko tradition for Xhosa boys. Explained to me by one Head, it requires the 16-year-old boys to spend a period of three weeks fending for themselves in the wild, at the end of which they are circumcised with a rock. From a western liberal perspective, this is abuse of a particularly horrific kind, but the history and traditions of peoples so long oppressed cannot easily be set aside.

Professor Murray Leibbrandt from the University of Cape Town spoke of his work on inequality. Again, the context was difficult: long-term decline in economic performance, limited room for increased social spending and population pressure as the 1990s bulge started to invert the demographic pyramid. Set against those trends, South Africa continues to spend a relatively large portion of its national wealth on education, and more children are now educated for longer. Their employment prospects, however, are poor and levels of inequality are massive. 60% of national income rests with the top 10% of earners and those educated to a degree or matric (A level) have a much higher chance of employment, but this remains a minority. The consequences of this educational deficit can be seen in levels of crime and drugs. Even in Cape Town, I was distressed to see families (with children) sleeping rough and scavenging in bins for food.

It was time to inject some optimism, so I went to listen to Tony Reeler, Head at Bishops, whose wonderful school I had visited on my second day in town. Tony took us on the Bishops’ story of ‘inclusivity in action’. Owning first his white, male privilege, Tony summarised his career and some of the dilemmas and problems of marrying transformation with strongly felt historic allegiances. In South Africa, ‘transformation’ refers to the post-apartheid government’s effort to create a more just, equitable and inclusive society by addressing the legacy of historical inequities, poverty and inequality. It was difficult to listen without being reminded of Dr Hanekon’s reference to William Bridges’ mantra that for something new to be born, something old must die. Tony and his fellow Heads are in the business of building bridges to the future rather than burning them. There were many takeaways, not least the need for courageous leadership, dialogue, reaching out to all communities and adapting the curriculum not least through Life Orientation and Diversity, Equity and Belonging classes. In South Africa (as reflected in the multi-lingual Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika) language is often key and simple ideas best, as with the iSAMS audio-recording of each boys’ name, so that staff and others would know how to pronounce it correctly. Changes are seldom without resistance and one example occurred when flying the pride flag to acknowledge the LGBTQ+ community. The simple expedient of a third flagpole ensured that the national and school flag could continue to be flown whilst acknowledging other identities and causes. If South Africa is to work it must work for all, something that Mandela recognised and symbolised like no other.

The undisputed highlight of the conference for me was Zolani Mahola, singer, storyteller and inspirational speaker, who burst onto the world stage with Waka Waka (This Time for Africa), the official song of the 2010 FIFA World Cup. Over an electrifying hour, she held her audience spellbound with the power of her story, her songs and her deep commitment to education. And then everyone was on their feet, learning songs and dancing (though I must confess the two-step shuffle I learned in Belfast didn’t quite cut it with this crowd.) Singing ‘I am joy’ together brought a real feeling of optimism to the conference and our conversation. No wonder the audience didn’t want to let her off the stage!

In addition to the conference, I was fortunate to visit six schools in my ten-day trip. They were admittedly not a representative selection of South African schools as the wonderful selection of leaders I met at SAHISA reminded me. All were independent, all single-sex (two girls and four boys) and all at the highest end of the fee range. They all had boarders, though only two were fully boarding schools with no day contingent. In any list of South Africa’s best schools, the schools I visited would appear at the top. Their facilities were incredible, their academic results strong and their commitment to holistic education unrivalled.

What probably strikes any visitor to a South African school is the exemplary manners of the pupils. As in 2002, small groups of students relaxing on the grass or by a bench would leap to their feet as you approached with a ‘good morning sir’. As you walked through a crowded courtyard or circulation space, ‘sirs’ would rattle through the air like machine guns, whilst every girl I met at St Anne’s greeted me with an engaging smile and ‘good afternoon’. Handshakes are firm and if you need help, it is immediately forthcoming. Doors were opened and questions answered. At Hilton, two matric (Y13) students, James and Jordan were commandeered at short notice to join me for lunch. If they were reluctant, there was no sign of it. Conversation was easy and the students were charming. One, James, had visited one of England’s foremost schools, but he had not been impressed. ‘No one greeted you’, he explained, ‘and the boys didn’t appear very communicative.’ I was somewhat embarrassed, though explained that sometimes English people found it hard to talk about much beyond the weather until getting to know someone. Perhaps some might see the culture of greeting as formulaic and potentially insincere, but first impressions matter and high expectations make a difference.

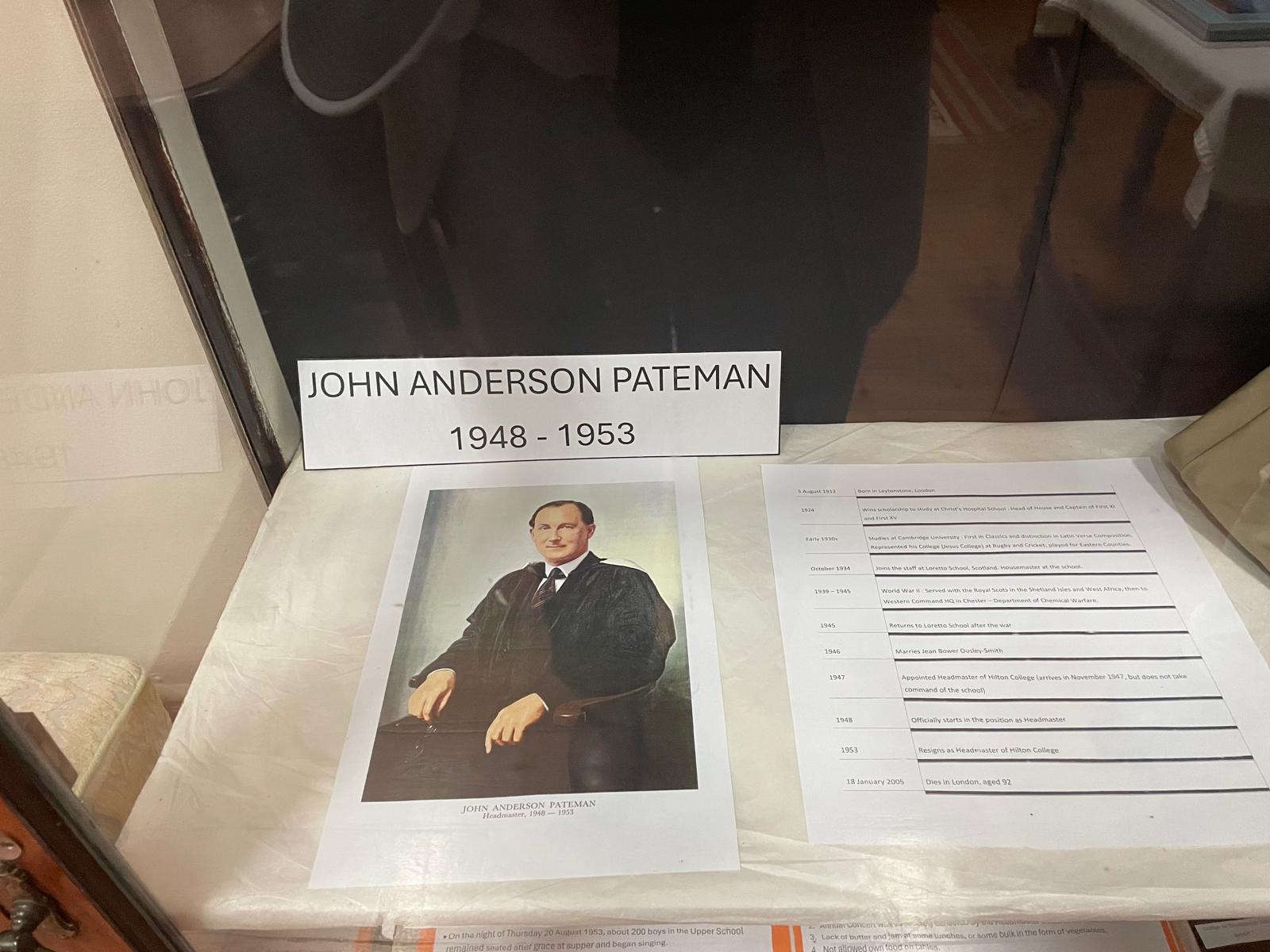

Despite their difficult history, South Africa’s schools are proud of their heritage if not always of their past. I met two extraordinary custodians of their schools’ history, who in different ways were bringing their schools’ stories to life. Bruce MacLachlan, longest serving member of the Hilton College staff is an information technology specialist, but his labour of love is clearly the college museum. Carefully selecting items of interest from the archives, he weaves narratives around pictures and objects thus unveiling the past to the present-day population of the school. The exhibition case devoted to former Head, John Anderson Pateman (1948-1953) proved so popular last year, that its place in the museum has been retained. Pateman’s tenure at Hilton was short-lived in the context of the time, facing a full-scale school rebellion in 1953 and a protracted legal case in 1950. A parent took the college to court when Pateman substituted a brush for the then ubiquitous cane to punish younger boys. Possibly intended as a progressive measure for the time, it nevertheless was not well received and yes, the actual brush in question is on display having been returned by the courts! A more conventional instrument of a mercifully bygone age is the rather terrifying cane displayed at Kearsney. Two punishment books reveal the variety of everyday transactions that might occasion its use with ‘lying down in class’ being one of the more unusual.

The investments of Michaelhouse and Bishops in their museums probably trump all others. At Bishops, Dr Paul Murray combines his encyclopaedic knowledge of the school with an accessible use of display boards to tell constructive stories of the way the school has changed, entirely aligned to the transformative agenda of the Head, Tony Reeler. Where there are museums, not far away are the facilities for former pupils and again Michaelhouse stands out for the scale of their investment. But one would be wrong to underestimate the importance of old boys and girls elsewhere. It was a theme to which we returned throughout my stay. For some, the involvement of former pupils was an issue, as with the boys who suggested that the school had been prioritising team over individual sports because the old boys wanted the school to win matches. On the other hand, Debbie Martin at St Anne’s, herself an alumna, told me how important the support of alumnae was to tackling ill-feeling in the wake of Black Lives Matter. For all heads perhaps, there is an equivocal relationship with former pupils. At once they are a source of great help and support to the school, sometimes financially and often through the all-important word of mouth, but they can be a drag on the need for change and in South Africa my sense was that their influence demanded much more time than most UK heads devoted to alumni, perhaps with the odd exception.

The costs of independent education is clearly as much on the minds of our South African colleagues as those in the UK. Demand for places remains high, but the facilities arms race so evident in HMC schools is no less apparent in South Africa. Hilton College, often decried or acclaimed (take your pick) as the country’s most expensive school, is immaculate. It is the first school I have visited with its own 4,500-acre game reserve, though the wildlife sensibly did not emerge in the midday sun for my visit. Each of the schools I visited has made a substantial investment in sport, not just for elite teams (though winning does matter here), but for a life-long commitment to physical and mental health as in Michaelhouse’s High Performance Centre, St Cyprian’s fabulous indoor pool and the manicured lawns and pitches at Bishops and Hilton. At St Anne’s Diocesan College in Hilton, it was good to see the wonderful water-based astro being used by boys from a local government school and others were equally committed to sharing their good fortune, including Bishops’ imaginative use of Mandela day to send their boys out into the locality to make a difference.

Some traditions sit a little less comfortably. There is still a strong sense of hierarchy in boys’ schools in particular. At Kearsney for example, this meant that eighth grade students (Y9) had to learn to recognise by name (surname) the whole of the matric class (Y13) in their first term at the school. When I commented a matric student explained to me the advantages and purpose of the tradition but was less certain when I enquired about any disadvantages. Evolution, however, is underway as the brilliant new pastoral deputy at Kearsney, Nkuli Gamede, asks the boys to reflect on different models of leadership, as exemplified by the equally brilliant Head, Patrick Lees. A tangible sign of this shift is physical: the refurbished boarding house common rooms replacing rows of chairs (with the oldest and tallest boys sitting at the front) with a more modern open plan feel, where groups of students from all years will be able to gather and connect.

The best part of any school visit is the chance to meet students, and I was incredibly lucky at St Cyps to be shown around by three young women from Grade 11 (Year 12), who were all about to take up leadership roles on the school executive. Their enthusiasm for their school was palpable and a characteristic of all the schools I visited was the tremendous pride students took in their school and appreciation for what the staff were doing for them. Again, at Kearsney, probably the highlight of my whole trip was the house music competition I attended on the evening of my arrival. It was a superb affair with the whole school, staff and parents in the audience and houses represented by choirs, ensembles, individuals and duets. The keyboard player playing with a blindfold was a masterstroke and the boys demonstrated that Kearsney’s rhythm was the equal to most SAHISA heads if not quite with Zolani Mahola’s vocal power.

If I am permitted one regret from my trip to South Africa, it would be that I only saw one full lesson. Marc Ancilotti, another of Patrick Lees’ brilliant deputies at Kearsney, was brave enough to share his Grade 11 (Y12) Maths lesson on the morning after house music. Marc is a fabulous teacher and a mathematician of some stature, so we were in safe hands and by the end of the lesson even I was piecing together bits of trigonometry long dormant, if not entirely defunct. The final year of High School in South Africa sees most students taking the NSC or National Senior Certificate. Students study at least seven subjects: two of the eleven official South African languages, mathematics, Life Orientation and three electives. Although access to some UK universities is possible with the NSC, a few schools offer international A levels alongside the South African qualification. St John’s Sixth Form in Johannesburg, whose Head I met at the SAHISA conference, is an interesting example, being a co-educational school within a distinguished boys’ school. Some boys transfer from the college, but boys and girls also join the Sixth Form directly, often heading to European universities, including Oxbridge.

One of the advantages of the absence of national examinations at the age of sixteen is that students can take three years for their NSC courses and enjoy rather greater freedom to innovate and explore. Michaelhouse’s ‘Future Fit’ curriculum is a case in point, and we will try to persuade Win de Wet, Deputy Rector, to share a little more about the programme with our education networks in due course. We also will want to learn more about the importance of the Ponderland experience and the C Block journey, these key rites of passage for South African students, which are both physically and mentally testing. At Hilton, the expedition takes the students to a mountain on the distant horizon from which they can look back at the gleaming white college buildings. On their return, they ring the college bell for the second of three times in their school experience, the final time on leaving after matriculation.

Finally, a huge thank you from me to colleagues in ISASA and SAHISA and, of course, the Heads and staff of Bishops, St Cyprians, Michaelhouse, St Anne’s, Hilton and Kearsney. Your hospitality and friendship have provided further happy memories of your wonderful country and hopefully forged great links for the future. Michaelhouse’s selection of Bart Wielenga, Head at Blundell’s, as Antony’s successor as Rector will also cement our relationship with our friends in the country and we look forward to Wayne Stuurman’s visit to our Conference in Wales. I can’t promise the weather, but a warm welcome is assured.