Blog

In celebration of research culture in HMC Schools: Introducing HMC’s Action Research Hub

Emma Hellyer

Head of Assessment and Innovation, HMC

Read the blog

Everyone at HMC is delighted to celebrate the launch of HMC’s new Action Research Hub in partnership with the University of Warwick.

The Hub will be led by HMC and Dr Nomisha Kurian, Assistant Professor in Education Studies, whose work has been recognised through the University of Cambridge Applied Research Award (2022) for bridging research and real-world educational practice, and questions how digital technologies, particularly AI, can best support children’s safety and wellbeing.

Given Dr Kurian’s commitment to the benefits of practitioner inquiry, we feel sure that the Hub will provide invaluable professional learning for colleagues, and facilitate a global network for sharing best practice, with pupil progress and wellbeing at its heart.

Establishing the importance of evidence-informed practice might seem uncontroversial, however it is worth reflecting that there has been considerable long-standing debate about what constitutes high-quality, rigorous research in education, and who should conduct it. Some suggest we should base our teaching practice on the best available ‘scientific’ evidence, with randomised controlled trials often perceived as the ‘gold standard’ (TES and the Education Endowment Foundation, 2023). The aim here is establishing ‘what works.’ Others caution against an instrumentalist approach to intervention. Nel Noddings, in her Philosophy of Education, was surely right to question methods which treat children as ‘interchangeable units to be considered as mere variables in an experiment’, and judicious to argue that the ‘rightness’ of the research depends on whether the form is appropriate.

In a seminal paper on the democratic deficit in educational research, Biesta conceptualised clearly what teachers already know – that we cannot control all the factors that determine learning.

"Nor can we measure in an ‘exhaustive’ way the quality of a learner’s achievement, since we cannot access the content of their minds."

Even if one could theoretically determine a causal connection between intervention and outcome, the intervention may not be intrinsically desirable. Education, therefore, must be considered a moral practice informed by children and young people’s best interests. Perhaps these factors have led some to cite the benefits of qualitative studies for helping us to understand why methods may meet with varying success in different classrooms, in different contexts, and with different pupils (Harley, 2024).

Enter action research, or practitioner inquiry.

Action research does not aim to make universal truth claims, but is typically understood as a context-specific intervention, with a very real commitment to improving practice. Rather than trying to persuade others that our intervention is the right one for all children and young people, we invite them to consider how the research findings might be applicable in different settings.

In this sense, action research tends to be democratic and collaborative. Rather than being positioned as passive recipients, teachers are empowered to engage critically with research literature and design research questions for their own settings. These practices may promote greater professional agency, and, in turn, wellbeing (Traianou et al., 2025).

Given its aim of safeguarding social and intellectual freedoms, action research may also appeal to colleagues with a moral commitment to the value of education and conducting research for social benefit (Mcniff and Whitehead, 2011). This is evidently the case at Pymble Ladies’ College, whose research institute recently published an action research report based on trauma-informed pedagogy, and meeting the unique needs of refugee students in mathematics education (Shaw and Way, 2025). It also aims to positively contribute to the number of women working in and leading research.

At Streatham and Clapham High School, several teachers are conducting research into improving the efficacy of homework, informed by the work of Jo Castelino (The Homework Conundrum, 2024) and Andrew Jones (Homework With Impact, 2021). This will inform the school’s homework policy and practices, following a careful evaluation of outcomes. Sarah Elliot, Assistant Head (Teaching & Learning), also supports all Year 2 Early Career Teachers to conduct reflective practitioner inquiries into aspects of their classroom practice they’d like to develop.

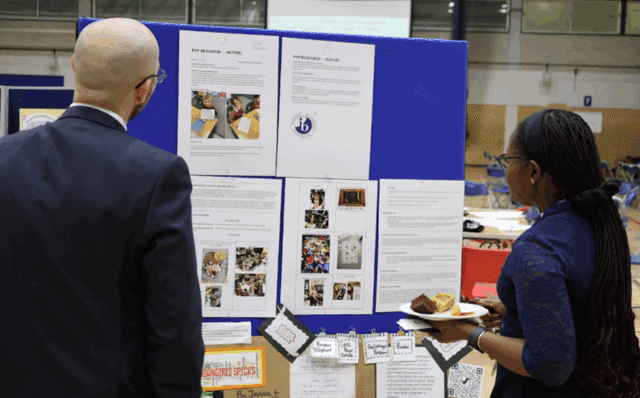

Colleagues gather to reflect on practitioner inquiry projects at Brentwood School’s annual Ideas Fair.

Brentwood School also cultivates a range of research strands and collaborative projects, with recent case studies seeking to encourage greater engagement among boys in dance and evaluate the impact of the IB Primary Years Programme inquiry-led approach to learning. Meanwhile, other HMC schools support colleagues to disseminate research findings which may challenge accepted educational norms or grapple with contested concepts. At St Albans School for instance, Rebecca D’Cruz (Head of Computer Science) challenges the notion of digital nativism in young people, with her recent MPhil research concluding that familiarity with AI does not equal competence in ‘critical evaluation, ethical reasoning, or understanding of the provenance of data, limitations, and risks of these systems.’

Colleagues gather to reflect on practitioner inquiry projects at Brentwood School’s annual Ideas Fair.

The new HMC Action Research Hub in partnership with the University of Warwick will seek to connect colleagues from across HMC’s global network to take part in cycles of practitioner inquiry, in small sets, supported by personalised mentoring. There will be various opportunities for collaboration and disseminating research findings, including a conference to share and celebrate completed projects.

Please find a list of